'WE LEAVE OR WE DIE'

Forced displacement under Syria's 'Reconciliation' agreements

Four local agreements negotiated by the Syrian government and armed opposition groups in 2016 and 2017 have led to the mass displacement of civilians across the country. These agreements were presented by the Syrian government and its allies as steps towards “reconciliation”, but, in reality, they were preceded by a pattern of prolonged sieges and bombardment that killed and injured hundreds of civilians and compelled thousands to surrender and evacuate.

Amnesty International’s research shows how Syrian government forces systematically subjected civilians to unlawful sieges and conducted air and ground assaults on civilians and civilian objects in a pattern of violations that amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity. It also shows how armed opposition groups committed war crimes by conducting their own unlawful sieges and indiscriminately shelling civilian areas.

Amnesty International has concluded that, in most instances, the mass displacement was not carried out for civilians’ security or an imperative military necessity and therefore also amounts to a war crime. As a result, thousands of civilians are living precarious existences. As talk of reconstruction in Syria increases, they should be allowed to return to their homes and provided reparation for the violations they have suffered.

Amnesty International’s research shows how Syrian government forces systematically subjected civilians to unlawful sieges and conducted air and ground assaults on civilians and civilian objects in a pattern of violations that amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity. It also shows how armed opposition groups committed war crimes by conducting their own unlawful sieges and indiscriminately shelling civilian areas.

Amnesty International has concluded that, in most instances, the mass displacement was not carried out for civilians’ security or an imperative military necessity and therefore also amounts to a war crime. As a result, thousands of civilians are living precarious existences. As talk of reconstruction in Syria increases, they should be allowed to return to their homes and provided reparation for the violations they have suffered.

'WE LEAVE OR WE DIE'

Forced displacement under Syria's 'Reconciliation' agreements

Al Waer

People displaced from al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs arrive at a Turkish Red Crescent camp in Jarablus in north-eastern Aleppo governorate on 19 March 2017. © Ensar Ozdemir/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The fourth batch of evacuees from al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs waits for buses to head to the north of Aleppo governorate on 8 April 2017, part of the staggered evacuation of more than 20,000 people. ©Firas Faham/Anadolu Agency/Getty Image

The fourth batch of evacuees from al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs waits for buses to head to the north of Aleppo governorate on 8 April 2017, part of the staggered evacuation of more than 20,000 people. ©Judy Arash/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The tenth batch of evacuees from al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs waits for buses to head to Idleb governorate on 15 May 2017, part of the staggered evacuation of more than 20,000 people. © Judy Arash/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Satellite imagery from 31 May 2017 (on the right) shows the new Zoghara camp in an area that was still empty on 19 March 2017 (see left-hand image). The camp, located approximately 250km north-east of al-Waer, along the border with Turkey, was quickly constructed to accommodate people from al-Waer.

A general view shows damaged buildings in al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs on 19 September 2016. ©Omar Sanadiki/Reuters

“If I had stayed, I would have been taken to fight for the regime. That’s the fate of young men who stay… No one left the neighbourhood willingly. Who leaves their home willingly? This was imposed on us… There is no way to guarantee the actions of the regime or the militias supporting it… people don’t feel safe to stay under the regime’s mercy.”

- Activist from al-Waer

- Activist from al-Waer

Siege and bombardment

- The government’s siege on the Homs city neighbourhood of al-Waer began in October 2013/

- The movement of the majority of al-Waer’s estimated 70,000-100,000 residents was arbitrarily restricted, and so was access to food, medicine and fuel. Even students and civil servants who were allowed in and out of the neighbourhood were often harassed at checkpoints and sometimes detained.

- The siege gradually worsened, particularly in 2016, during which bread was completely prevented from entering, prompting besieged residents to grind grains they received in aid parcels to make the crucial food staple.

- Al-Waer's residents ended up becoming heavily dependent on intermittent deliveries of aid, which fell short of covering the population's needs.

- At the same time, Syrian government air and ground attacks targeted residential neighbourhoods, medical facilities, even striking a playground.

- The movement of the majority of al-Waer’s estimated 70,000-100,000 residents was arbitrarily restricted, and so was access to food, medicine and fuel. Even students and civil servants who were allowed in and out of the neighbourhood were often harassed at checkpoints and sometimes detained.

- The siege gradually worsened, particularly in 2016, during which bread was completely prevented from entering, prompting besieged residents to grind grains they received in aid parcels to make the crucial food staple.

- Al-Waer's residents ended up becoming heavily dependent on intermittent deliveries of aid, which fell short of covering the population's needs.

- At the same time, Syrian government air and ground attacks targeted residential neighbourhoods, medical facilities, even striking a playground.

Parties involved in the negotiations

Russian military representatives, Syrian security officials, and a negotiating committee representing al-Waer’s civilians and fighters.

Agreement

In March 2017, a Russian-sponsored deal brought the district back under government control and resulted in the staggered evacuation of 20,000 residents, including all remaining fighters. Although the government did not explicitly order civilians to evacuate, those who left insisted that the actions of the government compelled them to do so. They said they feared retaliation if they stayed, and cited previous examples of detentions and disappearances following similar agreements in Homs and elsewhere. Many evacuees also said they left to avoid being forced to serve in the Syrian army.

Displacement

The evacuations took place from 18 March to 21 May. Twelve batches of evacuees headed to three opposition-held destinations: the north of Aleppo governorate, the north of Homs governorate, and Idleb governorate.

Post-evacuation

- Many evacuees are scattered between makeshift settlements and tent encampments that lack basic necessities. Some of the most challenging humanitarian conditions are being experienced by the estimated 7,500 displaced persons living in Zoghara camp in north-eastern Aleppo governorate. Poor conditions in the camp prompted an estimated 600 people to ask the government to go back to al-Waer.

- The government has also seized the homes of some displaced persons after they left because they were labelled as “wanted”, further throwing into question their ability to ever return.

- The government has also seized the homes of some displaced persons after they left because they were labelled as “wanted”, further throwing into question their ability to ever return.

FOUR TOWNS

Syrian officials attend a ceremony at Aleppo's military hospital on 25 April 2017 for the victims of a car bombing that targeted a convoy of buses carrying evacuees from the besieged towns of Kefraya and Foua. ©George Ourfalian /AFP/Getty Images

People injured in a car bombing that targeted buses carrying evacuees from the besieged towns of Kefraya and Foua, wait in a tent on the Syrian-Turkish border in Idleb on 17 April 2017. © Omar Haj Kadour /AFP/Getty Images

Bus in opposition-held Rashidin neighbourhood of Aleppo damaged by a car bombing targeting a convoy of people evacuated from Kefraya and Foua on 15 April 2017. © Omar Haj Kadour/AFP/Getty Images

Syrian Red Crescent paramedics wait for the buses evacuating civilians from the government-held villages of Kefraya and Foua, on 14 April 14 2017. © George Ourfalian /AFP/Getty Images

A member of pro-government forces stands at the entrance of the besieged rebel-held Syrian town of Madaya as residents wait for a Syrian Arab Red Crescent aid convoy on 14 January 2016. © Louai Beshara/ AFP/Getty

People in the besieged town of Madaya wait for the arrival of an aid convoy on 11 January 2016, as part of a six-month ceasefire agreement reached in September 2016. ©Stringer/AFP/Getty Images

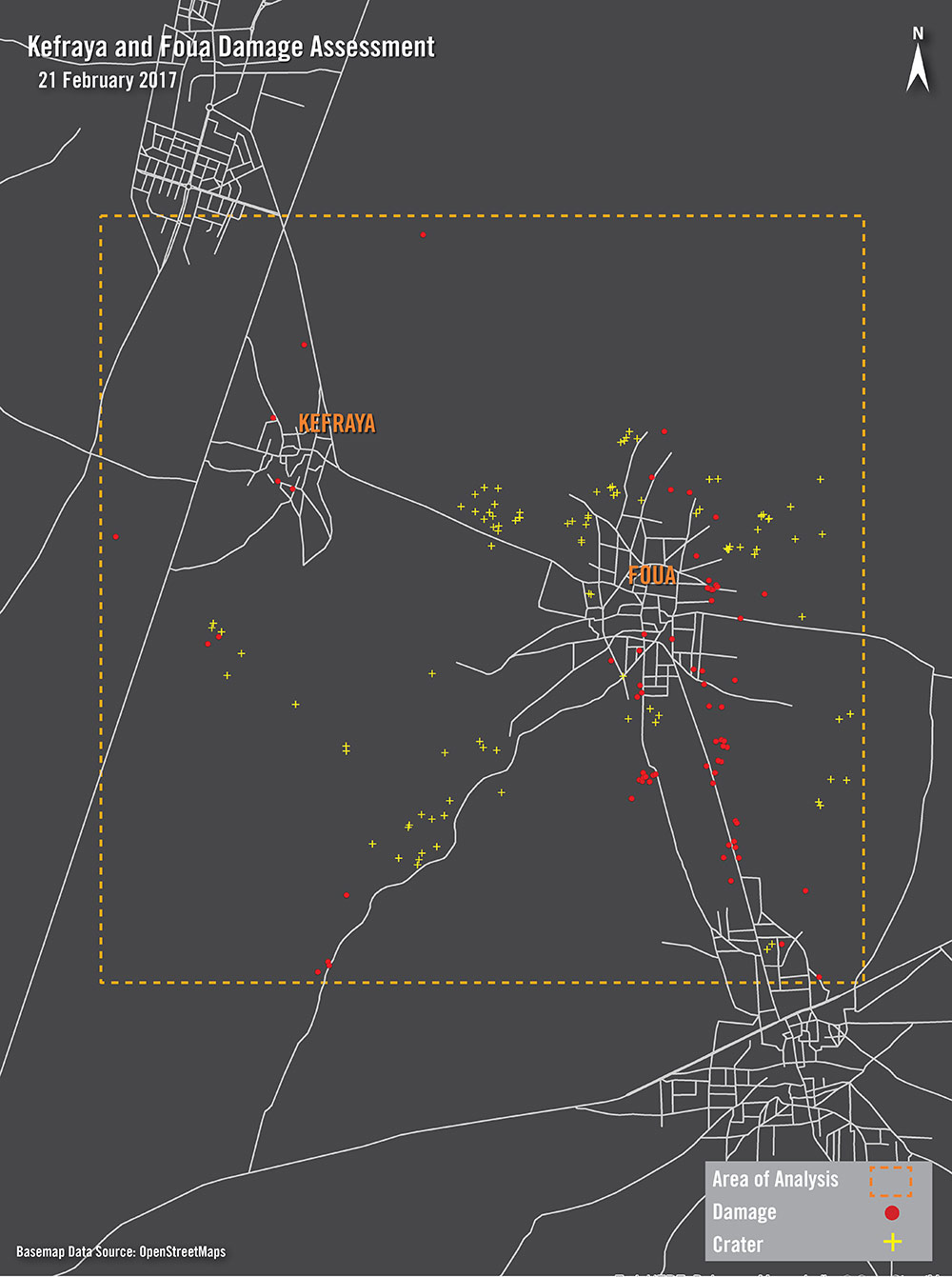

Analysis of satellite imagery from 21 February 2017 showing 72 structures damaged or destroyed and over 100 craters in an area of land of 25km2 in and around Kefraya and Foua.

“We used to follow the news all day and all night. We wouldn’t leave our homes when we read that someone had died in Kefraya and Foua from the shelling. If you had injured people in Kefraya and Foua, it meant we would have injured people as well. The snipers would get active every time there was an attack on Kefraya and Foua.”

-A teacher from Madaya

-A teacher from Madaya

“Every time the Syrian government attacked a place, we would be attacked. If [the planet] Mars was attacked, Kefraya and Foua would be attacked. The armed groups released their frustration and tension on us every chance they got.”

-A nurse from Foua

-A nurse from Foua

Siege and bombardment

- Several armed opposition groups, primarily Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and the Ahrar al-Sham Islamic Movement, began to besiege Kefraya and Foua, two adjacent, predominantly Shi’a towns in Idleb governorate, in March 2015. Some 400km away, Syrian government and allied forces started to besiege Madaya and Zabadani, in the governorate of Damascus Countryside, in July 2015.

- The Syrian government on the one hand, and armed opposition groups, on the other, sealed every entrance to the towns they besieged with checkpoints, preventing the entry of food, medicine or other basic necessities, restricting access to humanitarian aid and prohibiting civilians from leaving the towns.

- The Syrian government and their allies prevented residents from accessing the agricultural fields by setting up checkpoints at the entrance. Armed opposition groups used similar tactics in Kefraya and Foua. They shelled agricultural fields surrounding both towns with bombs whose explosions burned crops and destroyed fields.

- Residents of Madaya, Kefraya and Foua had to rely on humanitarian aid in order to survive. But that access was contingent on the approval of the Syrian government and armed opposition groups; in other words, the Syrian government only allowed UN access to Madaya and Zabadani if the armed opposition groups did the same in Kefraya and Foua, and vice versa.

- Syrian government and allied forces, including Hezbollah, repeatedly targeted civilians in Madaya during the siege, killing and injuring scores of civilians. Snipers positioned at checkpoints which encircled the town targeted civilians in the streets and near their homes.

- Armed opposition groups attacked and shelled civilian areas in Foua, killing and injuring civilians and destroying and damaging civilian objects. Armed groups shelled the towns using projectiles fitted with gas canisters known as "hell cannons", improvised rocket assisted munitions (IRAMs) known as "elephant rockets", mortars and Grad-type rockets fired from improvised launchers.

- The Syrian government on the one hand, and armed opposition groups, on the other, sealed every entrance to the towns they besieged with checkpoints, preventing the entry of food, medicine or other basic necessities, restricting access to humanitarian aid and prohibiting civilians from leaving the towns.

- The Syrian government and their allies prevented residents from accessing the agricultural fields by setting up checkpoints at the entrance. Armed opposition groups used similar tactics in Kefraya and Foua. They shelled agricultural fields surrounding both towns with bombs whose explosions burned crops and destroyed fields.

- Residents of Madaya, Kefraya and Foua had to rely on humanitarian aid in order to survive. But that access was contingent on the approval of the Syrian government and armed opposition groups; in other words, the Syrian government only allowed UN access to Madaya and Zabadani if the armed opposition groups did the same in Kefraya and Foua, and vice versa.

- Syrian government and allied forces, including Hezbollah, repeatedly targeted civilians in Madaya during the siege, killing and injuring scores of civilians. Snipers positioned at checkpoints which encircled the town targeted civilians in the streets and near their homes.

- Armed opposition groups attacked and shelled civilian areas in Foua, killing and injuring civilians and destroying and damaging civilian objects. Armed groups shelled the towns using projectiles fitted with gas canisters known as "hell cannons", improvised rocket assisted munitions (IRAMs) known as "elephant rockets", mortars and Grad-type rockets fired from improvised launchers.

Parties involved in the negotiations

Iran and Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham.

Agreement

In March 2017, parties to the conflict reached an agreement under the auspices of foreign governments, including Iran and Qatar. The agreement, which was known as the “four towns” deal and meant to lift the sieges, stipulated the complete evacuation of fighters and civilians from Kefraya and Foua, as well as the evacuation of fighters from Madaya, Zabadani and Yarmouk, a Palestinian camp inside Damascus besieged by the Syrian government.

Displacement

On 14 April, 75 buses transferred 5,000 people from Kefraya and Foua to a transit area in the opposition-held Rashidin neighbourhood of Aleppo while 60 buses transferred 2,350 people from Madaya to a transit area in the government-held Ramouseh suburb of Aleppo. Those from Kefraya and Foua were then supposed to cross into government-controlled Aleppo city and those from Madaya to opposition-controlled Idleb governorate. On 19 April, an additional 400 people evacuated from Madaya and Zabadani to Idleb governorate and 3,000 people evacuated from Kefraya and Foua to government-controlled Aleppo city. The Ahrar al-Sham Islamic Movement and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham continue to besiege Kefraya and Foua, where some 8,000 civilians and fighters continue to live, after the evacuation of fighters from Yarmouk faltered.

Violations during evacuation

On 15 April 2017, a day after the evacuation of the four towns started, a car explosion targeting a convoy leaving Kefraya and Foua, which was awaiting transfer from the opposition-held Rashidin neighbourhood of Aleppo to a government-controlled area, killed 125 people, including 67 children, and wounded 413 others. Several people, including children, remain missing following the explosion.

Post-evacuation

The Syrian government provided displaced families from Kefraya and Foua with financial assistance to cover rent and other expenses but has not informed the families for how long the assistance will continue. People displaced from Madaya have not been compensated by the government and have had to cover their own rent and other expenses or rely on local humanitarian organizations.

EASTERN ALEPPO CITY

A picture taken on 5 December 2016 shows destroyed buildings in al-Shaar neighbourhood in eastern Aleppo city as the Syrian government advances towards the area. © George Ourfalian / AFP/ Getty Images

A general view shows damaged buildings in Aleppo's Old City on 9 December 2016. © George Ourfalian/ AFP/ Getty Images

A convoy including buses and ambulances, evacuates civilians from eastern Aleppo city on 15 December 2016. © Ibrahim Ebu Leys/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Civilians in eastern Aleppo city, under siege by the Syrian government, wait to be evacuated on 15 December 2016. © Mamun Ebu Omer/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

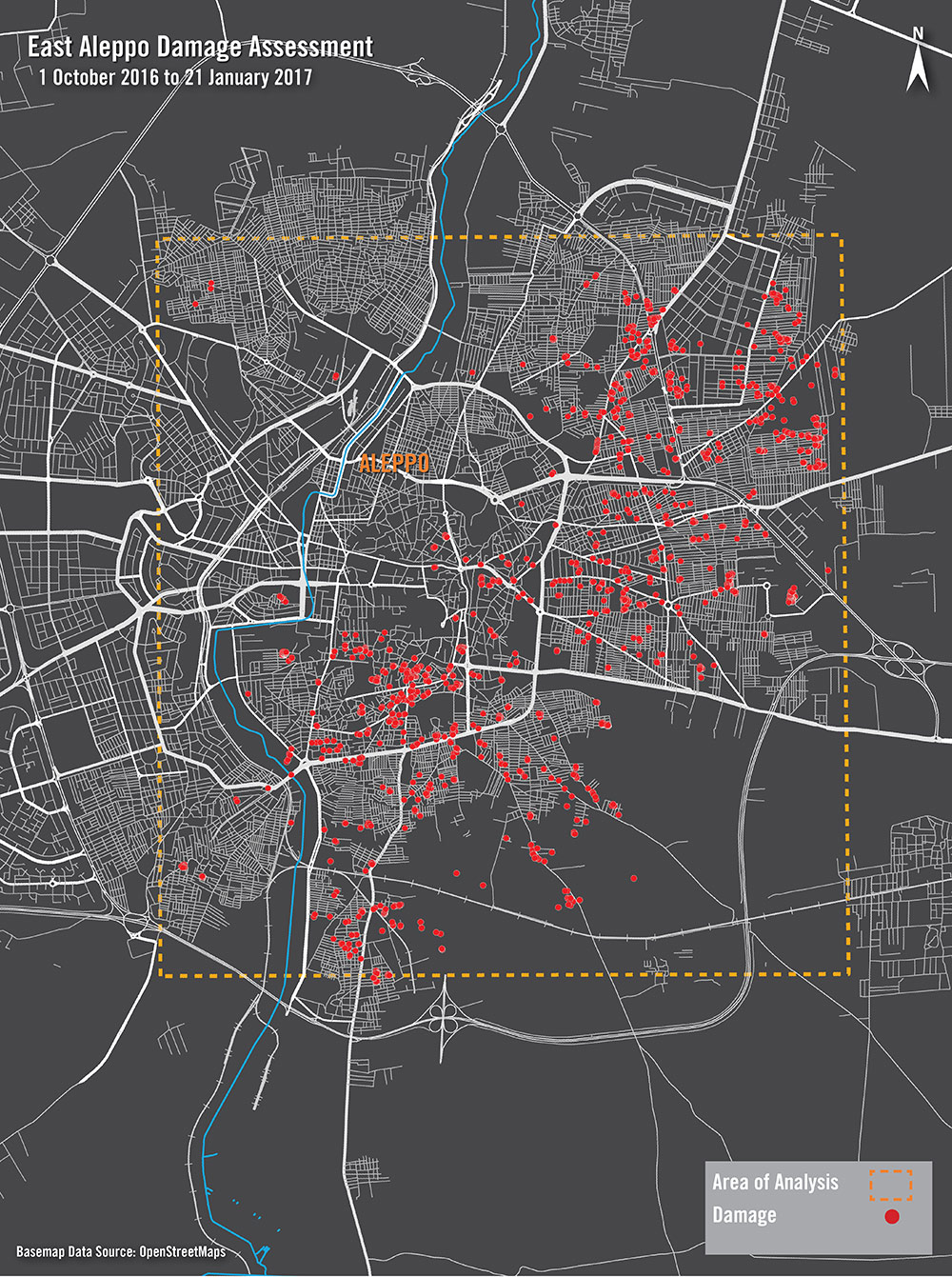

Satellite imagery analysis comparing data from 18 September, 25 September and 1 October 2016, and showing structures in an area of eastern Aleppo city of 65km2 that were damaged or destroyed between 18 and 25 September (at least 90) and between 25 September and 1 October (more than another 20).

“I have lived all my life in Aleppo city… I lost [my daughter]... A bomb fell in front of the building where she was playing. I can’t remember the last words she told me… I lost her just like that for nothing… absolutely nothing. I wish I had died with her.”

–A mother of two

–A mother of two

Siege and bombardment

- On 7 July 2016, the Syrian government began to besiege eastern Aleppo city, trapping its estimated 250,000 to 275,000 people, the vast majority civilians.

- The Syrian government restricted access to food, medicine and other crucial supplies.

- Syrian and Russian government forces carried out attacks on civilians and civilian objects using air-delivered munitions, internationally banned cluster munitions and incendiary weapons. The attacks targeted populated neighbourhoods, striking residential buildings, markets and hospitals, inside the city and far away from the front lines and with no military objectives in the vicinity.

- The Syrian government restricted access to food, medicine and other crucial supplies.

- Syrian and Russian government forces carried out attacks on civilians and civilian objects using air-delivered munitions, internationally banned cluster munitions and incendiary weapons. The attacks targeted populated neighbourhoods, striking residential buildings, markets and hospitals, inside the city and far away from the front lines and with no military objectives in the vicinity.

Parties involved in the negotiations

Ahrar al-Sham Islamic Movement and a Russian representative.

Agreement

On 13 December, an agreement was reached between the parties involving the evacuation of all armed group fighters to the north of Aleppo governorate. While civilians were not ordered to leave under the terms of the agreement, the vast majority of the estimated 37,000 residents at the time chose to evacuate due to the horrors to which they had been subjected in the preceding months as well as scepticism over the government's promises of safety.

Displacement

Armed groups and civilians were displaced to Aleppo and Idleb governorates.

Violations during evacuation

- On 15 December 2016, a convoy transferring ill and wounded people was subjected to indiscriminate shooting allegedly carried out by pro-government forces, injuring three people.

- On 16 December 2016, pro-government forces blocked a convoy transferring civilians and opposition fighters from continuing its journey, ordered scores of men to step out of the buses and cars, separating them from the women and children, and forced them to lie on their stomachs facing the road. The pro-government forces first fired in the air then shot at the men, killing and injuring several of them.

- On 16 December 2016, pro-government forces blocked a convoy transferring civilians and opposition fighters from continuing its journey, ordered scores of men to step out of the buses and cars, separating them from the women and children, and forced them to lie on their stomachs facing the road. The pro-government forces first fired in the air then shot at the men, killing and injuring several of them.

Post-evacuation

Residents displaced to Aleppo and Idleb governorates, continue to live in very difficult circumstances due to the limited access to humanitarian aid and the lack of employment opportunities. The vast majority of former residents of eastern Aleppo city interviewed by Amnesty International are paying for rent, water and other services, while others have found families to host them. According to journalists who visited Aleppo city in 2017, reconstruction of the Old City has begun while the rest of the neighbourhoods still lie in ruins.

DARAYA

Image of destruction in Daraya, posted on 10 August 2017. © Local Council of the City of Daraya / Facebook

Image of destruction in Daraya, posted on 18 August 2017. © Local Council of the City of Daraya / Facebook

Image of an alleged air strike attack in Daraya, posted on 16 August 2017. © Local Council of the City of Daraya / Facebook

Image of people evacuating from Daraya, posted on 26 August 2017. © Local Council of the City of Daraya / Facebook

Residents take stock of the destruction caused by a reported air strike attack by Syrian government forces on Daraya, southwest of the capital Damascus, on 25 January 2014. ©/AFP/Getty Images

An alleged barrel bomb purportedly dropped by a Syrian military helicopter explodes in the city of Daraya, southwest of the capital Damascus on 31 January 2014. © Fadi Dirani/ AFP/ Getty Images

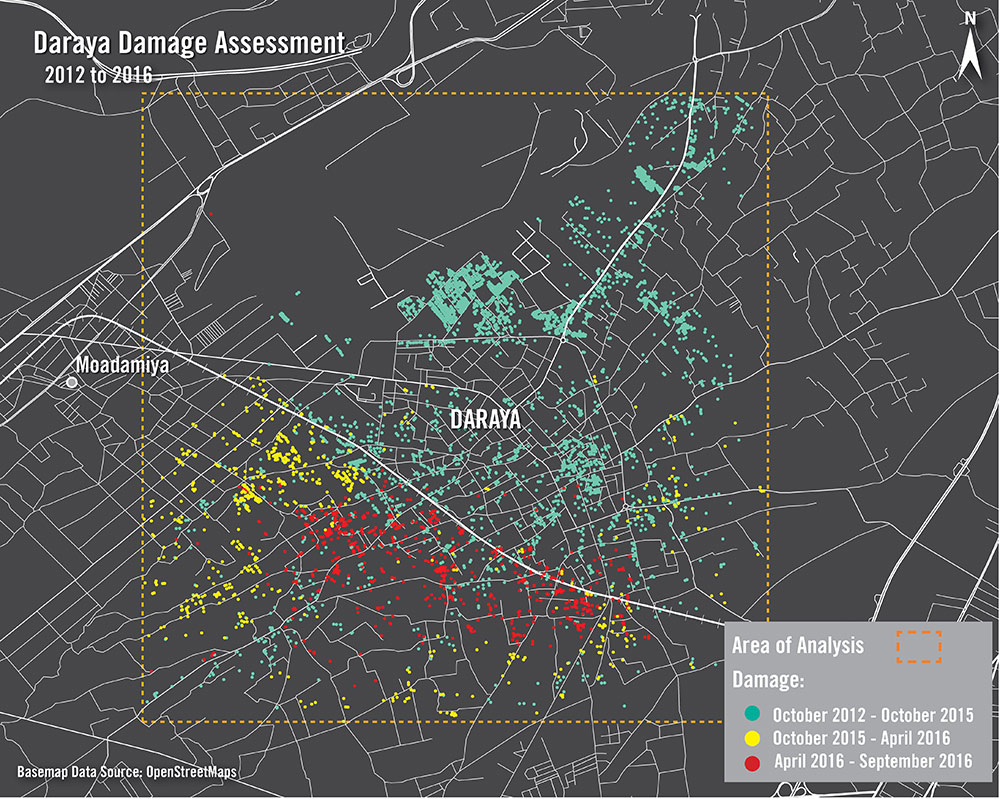

Satellite imagery analysis shows damage assessment in Daraya over 25km² between October 2012 and September 2016.

The right satellite image from 31 October 2015 shows a significant decline in healthy vegetation (illustrated in red hues) south-west of central Daraya compared to that visible in the satellite image on the left from 6 October 2012, indicating the widespread destruction of crops.

“Hunger really took its toll on [the students]. It was the hardest thing to see these little boys so skinny, so weak… It broke our hearts listening to their stories – one time one of the boys said he wished he would die like his father so he could finally get to eat in heaven.”

- Teacher from Daraya

- Teacher from Daraya

Siege and bombardment

- In November 2012, the Syrian government imposed a siege on an estimated 7,000 people living in the Damascus suburb of Daraya.

- The siege lasted for four years during which civilians were starved, causing some to resort to eating grass. The government unlawfully blocked or arbitrarily restricted access to basic necessities, including food, water, medicine, electricity, fuel, and communications.

- The situation was compounded by the military’s scorched-earth tactics of burning fields. Government forces also carried out direct attacks on civilians and civilian objects, including Daraya’s sole hospital, and indiscriminate attacks, using a variety of weapons such as barrel bombs and incendiary weapons.

- The Syrian government also repeatedly refused to allow UN humanitarian aid convoys to enter Daraya except on two occasions two months before the city was fully evacuated.

- The siege lasted for four years during which civilians were starved, causing some to resort to eating grass. The government unlawfully blocked or arbitrarily restricted access to basic necessities, including food, water, medicine, electricity, fuel, and communications.

- The situation was compounded by the military’s scorched-earth tactics of burning fields. Government forces also carried out direct attacks on civilians and civilian objects, including Daraya’s sole hospital, and indiscriminate attacks, using a variety of weapons such as barrel bombs and incendiary weapons.

- The Syrian government also repeatedly refused to allow UN humanitarian aid convoys to enter Daraya except on two occasions two months before the city was fully evacuated.

Parties involved in the negotiations

The Syrian government (represented by a state television presenter) and a committee representing Daraya's civilians and fighters.

Agreement

On 26 and 27 August 2016, the entire city’s remaining population – estimated to be between 2,500 and 4,000 – was evacuated under a local deal between the government and a committee representing Daraya’s civilians and fighters.

Displacement

The agreement did not give armed groups or civilians any other option but to leave the city to rebel-held Idleb or to al-Horjela government evacuation centre near Damascus. This forced displacement was not ordered for civilians’ own security or imperative military reasons and therefore violated international humanitarian law.

Post-evacuation

- Government forces were seen looting homes and properties after the evacuation.

- Former residents who were displaced to the rebel-held areas are struggling to make ends meet. Scattered around different parts of Idleb governorate, including Idleb city and camps in rural areas, they are largely dependent on aid.

- As for those who evacuated to the government shelter, some of them do not seem to have been spared retribution as the agreement stipulated. Despite undergoing a security screening, a number of these evacuees, mostly women and children, have been arrested at checkpoints in the Damascus suburbs when they have moved around or tried to travel.

- Former residents who were displaced to the rebel-held areas are struggling to make ends meet. Scattered around different parts of Idleb governorate, including Idleb city and camps in rural areas, they are largely dependent on aid.

- As for those who evacuated to the government shelter, some of them do not seem to have been spared retribution as the agreement stipulated. Despite undergoing a security screening, a number of these evacuees, mostly women and children, have been arrested at checkpoints in the Damascus suburbs when they have moved around or tried to travel.